Johnny Most

http://vault.sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1119051/index.htm

A Raspy Voice, A Hacking Cough And 'havlicek Stole The Ball!'

William Taaffe

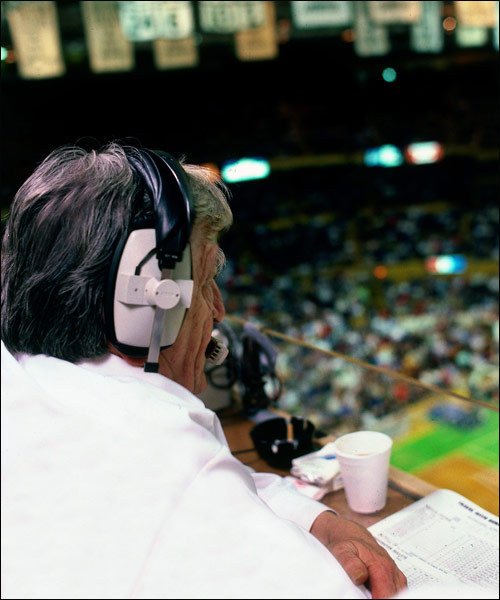

"This is Johnny Most high above courtside at the Boston Garden...."

In the sports lexicon, there are two types of homers: homer as in round-tripper, and homer as in biased broadcaster. Johnny Most—irascible, loyal, prejudiced, wonderful Johnny Most—has been announcing Boston Celtic games on the radio since 1953, a few years after they took down the peach baskets over in Springfield, and he is, without question, the ultimate homer. In his green-tinged view of reality on WRKO, every Celtic player is conceived without sin. All others—refs, opposing players, loudmouthed patrons, in Philadelphia especially—are corrupt.

You know what Johnny's 32-year record of distortion has gotten him? Love. You could feel it last Friday evening when he hosted Red Auerbach night at Boston Garden. Boston fans identify with no one, not even the great Cooz, more than Johnny. A kind of cult following has developed among the fans, who tune in just to hear what he'll say next.

Most, who in his early days worked in New York under Bill Stern, has all but ignored TV since Auerbach hired him eons ago. His whole life is radio and the team, for which he has broadcast on five different stations. He's a throwback to another age, when sports announcers were characters, not clones.

One thing different about Most, 61, is his voice, which three generations of fans have learned to imitate. His "Havlicek stole the ball!"—describing John Havlicek's theft of a Hal Greer inbounds pass in the 1965 playoffs against Philadelphia—is probably the Most quoted line. The voice may have been melodious once, but now it's a bark, raspy and urgent, from the back of the throat. For his entire adult life Johnny has been a two-pack-a-day cigarette man—"According to the Surgeon General, I've been dead since 1955," he says—and there are times you can hear him hacking away, hand over mike. If fans in enemy cities stand in front of his position, he'll interrupt his play-by-play to yell at them to "smarten up" or even swat them away with his good hand (his right hand was paralyzed by a stroke he suffered in 1983). Nothing gets in the way of his broadcast. While calling a 1959 playoff game he lost his dental plate, but he says, "I caught it before it fell over the balcony."

Then there's Most's legendary preparation. As in zero. For more than 2,500 games he's brought nothing to the task except a program insert, cigarettes, three or four cups of coffee and "vapor-action" throat lozenges. If a new enemy player is unfortunate enough to be surnamed Jones or Brown, Johnny will make no effort to learn his first name.

Although Most keeps up on the action with his rat-a-tat call and does give credit for outstanding plays made against the Celtics, he's the world's greatest embellisher. The refs pamper the opposition while the Celtics always get mugged. A typical Most game is part basketball, part morality play, part championship wrestling. "People in Boston don't consider a basketball broadcast a basketball broadcast without him," says former Celtic Tommy Heinsohn.

"I'm a one-way street, no question about it," Most says. In the extremely unlikely case any Celtic does something naughty, "I usually find reasonable provocation for that naughtiness." Ask Most if he could make it starting out today in broadcasting, and he's likely to swat you one: "Some professor sits back in a university somewhere and says, 'Thou shalt not be prejudiced.' I wanna know why not? Why can't I be? You can't be with a bunch of guys day in day out, year in year out, and not have affection for them. And if you don't broadcast that way, you're lying."

Most's good-guy, bad-guy outlook can backfire on him, though, when a former villain is traded to the Celtics, or a Boston hero is sent to another team. Because the world is populated by brutes, "big crybabies" and other assorted black hats playing for enemy teams, and because all Celtics are paragons of virtue, this presents a problem. Year before last, for example, Rick Robey, who had been a white hat, was traded to Phoenix for Dennis Johnson, whom Johnny had been calling "Mr. Nasty." Overnight, Robey became the "Baby-faced Assassin" and D.J. became a sweetheart. "There was a mending of D.J.'s ways the moment he came to Boston," Most explains. "That's the angelic influence we have on people." Johnny dubbed Moses Malone "Big Coward" for scuffling with Larry Bird last November. Some other sobriquets applied by Most over the years: The Brat (Rick Barry) and Roughhouse Rudy (Rudy LaRusso).

On the side, Most writes free verse. His best poem goes like this: "With the passage of time, the pretty flower wilts and the green green grass is yellowed, but the beauty within me matures and grows, with the passage of time." With Johnny, you never know what to expect. To paraphrase one of his fans, Bob Ryan of The Boston Globe, the only thing worse than having heard Johnny Most is never having heard him.

http://www.celtic-nation.com/interviews/johnny_most/02_21_2005_johnny_most.htm

Johnny Most - The Jamie Most, Mike Carey Interview

By: Michael D. McClellan | Monday, February 21st 2005

It was a marriage and a love affair all rolled into one, this thing between Johnny Most and the Boston Celtics, a relationship so rich with passion that the two have become inextricably linked, radio broadcaster and storied franchise, a pairing unmatched in the history of professional sports. Most was there in the early days when Walter Brown’s Celtics were struggling to remain economically viable, calling games from high above courtside in the Boston Garden, while a young coach named Red Auerbach barked commands to future hall-of-fame players named Sharman, Cousy and “Easy” Ed Macauley. These were heady days, pre-dynasty, and Most was arguably the man most responsible for spreading the Celtics’ hoop gospel. He called the games from his heart. He loved the team, and it shone through in his unique broadcasting style. He made people take an interest. He saw the games the way George W would have us see the War on Terror, with no shades of gray and a very clear delineation between hero and villain, and in the process we found ourselves sharing this passion with Johnny Most, who we came to recognize as the Boston Celtics’ singular voice and the team’s Number One Fan.

The basketball landscape in the 1950s was vastly different from the corporate giant that exists today. Back then, teams and owners did whatever they could to survive. From playing promotional games at midnight – the Milkman’s Matinee in the Boston Garden is perhaps the most famous example – to barnstorming throughout New England, playing twenty games in as many nights, the Celtics were at the forefront of this grassroots marketing campaign. Brown, a hockey man, was convinced that professional basketball would succeed on a grand scale. He also knew that there would be tough times, as indeed there were: Brown would mortgage his home just to keep the franchise afloat, and there were times when players were asked to wait on paychecks because there simply wasn’t enough money to pay the bills. Most, who began calling games in 1953, saw all of this unfold. He knew that the average New Englander viewed the NBA in general – and the Celtics in particular – as second rate entertainment. If they wanted to watch basketball, they would take in a Holy Cross game. If they wanted a real sport, there was always the Red Sox or the Bruins. He also knew that the team needed a voice, especially if the Celtics were to gain a foothold in the consciousness of the average Bostonian.

Johnny Most decided very early on to be that voice. A self-proclaimed ‘homer’, Most was unapologetic in the way he called the games. If you were a Boston Celtic, you could do no wrong; if you were the opposition, then you were Public Enemy Number One. Under Most’s watchful eye, the Celtics never lost a game – they simply ran out of time. It was a style borne of that era, during a time when a true family atmosphere permeated all NBA franchises, and Most was as much a part of the Boston Celtics as the leprechaun himself. He rode the bus with the team when they went on those barnstorming tours, and he roomed with players on the road during the regular season. And fans began to take notice; Bob Cousy became “Rapid Robert” because of Most, and phrases such as “fiddles and diddles” and “stops and pops” worked their way into the lexicon of anyone who tuned into Most’s radio broadcasts.

By the time Bill Russell arrived midway through the 1956-57 season, Most had established a loyal base of listeners and the Celtics had turned the corner in terms of turning a profit. Tommy Heinsohn was the other impact rookie on that team, and through the years he would become one of Most’s closest friends. With all of the pieces coming together, Most continued calling the games with his unique passion. So vivid was his play-calling that TV did little to encroach on his popularity; even when the games were televised, an overwhelming number of fans chose to turn down the volume on their TVs and turn on the radio broadcast instead, as Most turned every home game into an epic struggle on the famed Boston Garden parquet. Russell, Cousy, Sharman and Heinsohn were transformed from basketball players to warriors, noble in cause, honorable in spirit, and by season’s end the first of the team’s sixteen championship banners was safely in hand.

More championships followed, including eight consecutive banners from 1959 to 1966, as more hall-of-fame talent was added to an already loaded roster. Sam Jones became the team’s most lethal offensive threat. K.C. Jones played alongside him in the backcourt, and Most quickly dubbed them “The Jones Boys”. John Havlicek supplanted Frank Ramsey as the team’s Sixth Man. It was an impressive march through history, as the greatest dynasty in NBA history – and arguably the greatest dynasty in any sport – showed no signs of slowing. The record streak of titles came perilously close to ending a year early, this in the 1965 Eastern Conference Finals against the Philadelphia 76ers, and circumstance puts Most in place to make one of the greatest calls any sport has ever known.

With mere seconds left and the Celtics clinging to a one-point lead, the Boston Garden faithful brace themselves for a potential streak-killing inbounds pass. The Celtics find themselves on their heels. Most finds himself high above courtside, on the edge of his seat, seconds away from history. And then it happens: Havlicek intercepts Hal Greer's inbounds pass, saving the day for the Celtic Dynasty and sending Most into a frenzy.

Most: "Greer is putting the ball into play. He gets it out deep…Havlicek steals it. Over to Sam Jones. Havlicek stole the ball! It's all over! Johnny Havlicek stole the ball!"

The call has been played and replayed through the years, representing a high water mark for Most while transforming him into cultural icon. That the reaction was a moment of pure, joyous passion only elevated the call further; one could hardly imagine Most’s predecessor, Curt Gowdy, losing his professional cool in such spectacular fashion. All of which cut to the very core of the Most Philosophy: Be yourself. Don’t be a phony. And Most wasn’t. What you saw – and what you heard – was exactly what you got. Most was not going to pretend to be someone he wasn’t, on the air or away from it. He was close to the players, knew them on a first-name basis, even the ones who were struggling to make the team. And in a way, he rooted even harder for those types of guys – the twelfth men, the Conner Henrys of the world – who were trying to become a part of the Celtic family. He didn’t pretend not to care. He wanted them to succeed as much as a Bill Russell, Dave Cowens, or Larry Bird.

Most was there when Red hung up the clipboard after the title streak reached eight. The year was 1966, and Russell was named player/coach. The aging Celtics, deprived of quality draft picks by constantly picking so low, remained a factor by adding bench strength via trade. Wayne Embry – so big that he was dubbed “The Wall” by Most – was brought in as a backup for Russell, while multitalented forward Bailey Howell was added for his offensive punch. Still, it wasn’t enough; the Celtics ran into a buzz saw in the form of the Philadelphia 76ers, and every expert from New York to Los Angeles proclaimed the dynasty over. Not even close; the Celtics won it all again in ’68, and then again in ’69 – Russell’s last season in a brilliant, hall-of-fame career.

That ’69 series against the Lakers was a classic, and pitted Russell against Wilt Chamberlain for the last time. It also brought the two greatest broadcasters together yet again – Most, and the legendary Chick Hearn, the Lakers’ radio personality. When they arrived at the Forum for Game 7, both broadcasters were surprised at what they saw: Team owner Jack Kent Cooke was so confident of a Laker victory that he’d arranged for thousands of celebratory balloons to be tied to the ceiling. He’d brought in the USC Trojan Marching Band. Cases of champagne were stacked high outside of the Laker locker room. The media were handed press releases before the game which began: “When (not if) the Lakers win the championship…”

All of which added up to the perfect motivation for the Russell, Sam Jones and the rest of the Celtics. Most and Hearn talked about it before the game, and both men knew that Cooke’s plan – his own victory cigar of sorts – could very easily blow up in his face. Even Auerbach, for all of his arrogance, knew that there was a time to light up, and that that time was never before the game had been played.

The game became famous for Wilt’s phantom injury, and his coach’s refusal to let him re-enter the game. Don Nelson launched the shot that hit rim, bounced straight up, and dropped cleanly through the net. Game, set, match. A jubilant Johnny Most was beside himself with joy.

“We busted their balloons,” he screamed. “The USC Band is packing their instruments and all the champagne has suddenly gone flat. And then there’s poor Wilt, who probably is icing his boo-boo right now while picking up a crying towel.”

Most’s disdain for Chamberlain was legendary. He viewed the Kansas University product as a stat monger, more concerned with getting his points than winning titles, and Most used every opportunity to take a jab at the Laker big man. “Wilt the Stilt” was a nickname that bothered Chamberlain a great deal, and Most used this to great advantage. He constantly referred to the seven-footer as “The Stilt”, a bit of on-air psychological warfare that Russell himself surely appreciated. And the nicknames, like the phrases he made famous, live on in Celtic lore. Villains such as Rick Mahorn and Jeff Ruland became “McFilthy and McNasty”, while the grinning, mischievous Isiah Thomas – another of Most’s most-despised – was often referred to as “Little Lord Fauntleroy”.

Most saw plenty during the 1970s, as Auerbach rebuilt the team around players such as Havlicek, Dave Cowens and Jo Jo White. Close friend Tommy Heinsohn was named head coach, and the Celtics put two more championship banners in the rafters of the Boston Garden. The ’74 crown came at the expense of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and the Milwaukee Bucks, while the ’76 banner was most notable for Game 5 against the Phoenix Suns. Now billed as “The Greatest Game Ever Played”, Most was there for that triple-overtime game in the intense Garden heat. The Celtics prevailed, and went on to win the team’s 13th world championship.

By 1979 the team was in disarray, but Auerbach was again working on another title run. Larry Bird was on the roster as a rookie, drafted the year before as a junior eligible, and Most was set to watch another era unfold. Kevin McHale and Robert Parish were added a year later, paving the way for three more championships. The NBA, in serious trouble just a few short years before, was suddenly brimming with a newfound popularity. A Golden Age was born. Players such as Julius Erving, Magic Johnson and Bird were making the league fan-friendly, Michael Jordan was on his way, and Johnny Most was right there to make the calls.

On the occasion when Erving and teammate Moses Malone attacked Bird out of frustration, Most wasted little time unleashing a torrent on Malone, whom he perceived as a coward for his role in the fracas. A sampling of that 1984 broadcast shows how excitable Most could be in the heat of the moment:

“I want to see him [Malone] fight Bird face-to-face…because he won’t fight anybody face-to-face…Malone came up from behind…a real, yellow, cowardly act…Malone is a coward – I mean I say that irrevocably – Malone is a coward!”

The 1986 NBA Finals brought another classic Most moment, this when Houston’s 7’-4” Ralph Sampson decided to take on Boston’s 6’-1” Jerry Sichting. In 1987, history repeated itself, as Bird’s steal in Game 5 of the Eastern Conference Finals helped save the series against the Detroit Pistons. Most was there for that call as well. He was there for virtually every piece of Celtics history, until his passing on January 3rd, 1993. His loss was felt not only by the Celtic Family, but by legions of Celtics fans the world over. To them, Johnny Most was as much a part of the fabric of the team as Auerbach, Cousy, Russell, Havlicek and Bird.

Johnny Most’s story is wonderfully told by two of the men who knew him best – his son, Jamie, and his close friend Mike Carey. The book “High Above Courtside” began at the request of Most, in 1984, as an autobiographical effort. Mr. Carey gladly agreed to be a part of this project, and began the process of interviewing those who knew him best. As Most’s health began to deteriorate, it became clear that the project would not be completed for some time. With the help of Jamie, “High Above Courtside – The Lost Memoirs of Johnny Most” was finally published in 2003. It is one of the finest books on basketball history ever written, a must-read for Boston Celtics fans everywhere. Both Mr. Carey and Mr. Most deserve a tremendous amount of credit for seeing this fine effort to fruition.

“Voice of the Celtics – Johnny Most’s Greatest Calls” represents their second collaborative effort, and is packaged with a CD of calls by the late broadcasting legend. The CD, narrated by Tommy Heinsohn, contains priceless audio tracks that are sure to bring as many chills as memories. It is the work of Jamie Most, who also uses his creative talent as a filmmaker in New York. The book is a collection of Johnny Most’s finest moments, from the classic calls to his relationships with Walter Brown and Red Auerbach. No stone is left unturned. “Voice of the Celtics” goes where “Courtside” leaves off, and the two volumes represent a comprehensive look at the love affair between Johnny Most and the Boston Celtics.

Celtic Nation recently had the pleasure of sitting down with Mike Carey and Jamie Most, each of whom deserve credit for “Voice of the Celtics” and “Courtside” We are honored to bring you this interview.

CELTIC-NATION

‘Voice of the Celtics’ is dedicated, in part, to Bob Brannum, one of the true “Good Guys”. I had the honor of interviewing Mr. Brannum and came away similarly impressed. Please tell me a little about Mr. Brannum, and what led you to dedicate this fine effort to him.

JAMIE MOST

Dad was more than just a play-by-play announcer or a radio broadcaster to Bob. The two of them became close during Bob’s playing days, and they remained lifelong friends after his retirement from the Celtics. Bob was the head counselor at Camp Milbrook when I was a child, so I remember being around him from a very early age. He was gruff on the outside, and that’s what many people remember most about him, but he was a very warm person on the inside. He really was a great guy once you got to know him. With Bob, it was truly a case of tough love. So Mike and I talked about it, and we thought that both Dad and the Brannum family would be honored if we dedicated the book to Bob, who has been battling cancer for the past couple of years. [Editor’s note: Sadly, Mr. Brannum passed away on February 5th, 2005, after a courageous fight against pancreatic cancer.]

MIKE CAREY

Yes, the dedication of ‘Voice of the Celtics” was a joint decision. Milbrook was the first summer camp with ties to the Celtics, and it was held close to Bob’s home in Marshfield (Massachusetts). Jamie was a camper there, so he got to know Bob very well over the years. I met him in 1981, when I was a young reporter and he was the basketball coach at Brandeis University. Bob was nice enough to help me – no question was considered stupid, and he never made me feel that I was wasting his time. He was very patient, and I learned a lot from him. So Jamie and I wanted to do something nice for him – in part to show our appreciation for all that he’d done for us over the years, and in part for the special relationship that he had with Johnny.

CELTIC-NATION

‘Voice of the Celtics’, and ‘High Above Courtside’ are must-read classics, not only for fans of the Boston Celtics but for anyone who wants a history lesson in professional basketball. What was it like for you to put these fine works together?

JM

As a son, “Voice of the Celtics” was a special way for me to pay tribute to my dad. It was my way of recognizing the great life that he led, some of which I took for granted while growing up. So it meant a lot for me to be a part of this project, especially producing the CD. I think it has really helped bring a sense of closure. For my children, this is a way for them to learn about their grandfather. They never had the thrill of knowing him, and now they have something that will keep him close as they grow up.

Producing the CD brought back so many memories – I started going to the games at a very young age, watching them by dad’s side while he worked. I didn’t really appreciate it all then because I was so young, but over time I came to realize just how special he was. I remember attending the Celtics’ family Christmas parties, having fun with the players, and watching the way the fans treated him. He was as much a part of the Celtic family as anyone.

MC

All of the credit goes to Jamie for “Voice of the Celtics”. He was so focused on seeing it become a reality, and he wasn’t going to take no for an answer. His work on the CD is phenomenal. It captures the true essence of Johnny Most – his passion for the Boston Celtics, his unique broadcasting style, and his self-deprecating humor. It’s also loaded with great calls – you’ll find “Havlicek stole the ball”, as well as a bunch of other classics from the glory days.

As far as the text for “Voice of the Celtics”, I didn’t want it to be a retelling of “High Above Courtside”. I added some information about Curt Gowdy, Johnny’s predecessor as play-by-play man for the Celtics, and also some background on Marty Glickman, who was both the Knicks and New York Football Giants play-by-play announcer when he “discovered” Johnny while listening to him over drinks at a bar. I also elaborated on Maurice Stokes, who Johnny felt was going to be one of the top five players in NBA history.

Producing “High Above Courtside” was very frustrating. In 1987, Johnny and I had a contract with a publisher, but that was around the time that Johnny became very sick and couldn’t actively promote the book. The publisher just didn’t think the book would sell without him pushing it. The manuscript sat on a book shelve for fourteen years until the original publisher finally agreed to release the book rights. It was frustrating, because Johnny Most was one of the game’s great characters. We felt it was a great story to tell, not only because of the great calls, but because many of the fans who listened to him didn’t know his background. They didn’t know about his New York roots, or about his affiliation with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Regardless of the struggles, I loved writing “High Above Courtside”. Fourteen years had passed since the manuscript was completed, and by then we had some great stores about Johnny as told by friends, colleagues, refs and foes alike. We added a section to the back of the book just for that. There are stories from everyone imaginable; Sam Jones, Chick Hearn, Dave Cowens, Rick Carlisle. You read them, and you realize just how deeply people cared for Johnny Most.

CELTIC-NATION

Johnny Most had a great relationship with nearly everyone in the Celtic Family. Tommy Heinsohn was one his closest friends, and provides the wonderful narration on the accompanying CD. Please tell me a little about Mr. Heinsohn, and his relationship with Mr. Most.?

JM

Dad and Tommy were the best of friends. Dave Cowens called them ‘Frick and Frack’ [laughs]. The two of them hit it off right away, and it wasn’t long before they were rooming together on road trips. Tommy was a history buff, and dad had served our country during World War II. They also had a lot of similar interests – dad liked to write poetry, and Tommy was an artist. They both liked boxing.

For me, it was very special growing up around the Heinsohn family. From my playing Pop Warner football to his teaching me to play basketball, Tommy has always been a big part of my life. I’ve become lifelong friends with his son, Paul. I’ve shared so many great memories with the Heinsohns. So when I decided to produce the CD, Tommy was the first and only person I ever really considered to do the narration. He accepted without hesitation. To him, it was an honor to be a part this tribute to my dad. They were lifelong friends, so he was the perfect choice.

MC

Johnny roomed with Don Barksdale when he joined the team. Barksdale was a tremendous athlete – he was twenty-eight when blacks started being drafted by NBA teams – and Johnny didn’t hesitate rooming with him on road trips. There wasn’t a prejudiced bone in his body. He would get very angry anytime the players were subjected to racism, and he didn’t hesitate to let his feelings be known.

After Don retired, Johnny, along with Celtic players Jack Nichols, Arnie Risen and Dwight “Red” Morrison rented a house in Revere. After they left, Johnny would frequently room with Tommy on the road. Johnny was from New York, Tommy from New Jersey. It didn’t take them long to become fast friends.

There is a funny story about these great men; when Tommy decided to go into broadcast journalism, he naturally asked Johnny for advice. Johnny said that being true to yourself was the most important thing to remember. Don’t be a phony. That was the main thing. And then, he looked at Tommy and said, “It doesn’t really matter anyway, because everyone is going to be listening to me!”

CELTIC-NATION

“Havlicek stole the ball” is arguably the greatest single call in the history of professional sports. The companion CD contains this classic moment, as well as a treasure-trove of other gems. Of all the great moments called, what were some of Mr. Most’s personal favorites?

JM

That’s a good question – I don’t know that I’ve ever asked him that. We talked about the great games, but we never really talked about his favorite moments as a broadcaster. I know that he was most proud of “Havlicek stole the ball”, because that was the call that really generated national exposure. Bird’s steal is another one of his favorites. “Voices of the Celtics” has a section about various Johnny Most stories, and the 1988 McDonald’s Classic stands out. Dad couldn’t pronounce the names of the Yugoslavians. It was really humorous, and the fans really got a kick out of it. Dad wasn’t embarrassed by it at all. He could poke fun at himself as well as anyone, and I think he saw the humor in that broadcast.

MC

I agree with Jamie – “Havlicek stole the ball” is Johnny’s signature call, the one that really put him on the map. Bird’s steal of Isiah’s inbounds pass is also right up there. He was also proud of his call during the 1984 NBA Finals, when Gerald Henderson stole the ball from James Worthy. So although he tried not to rank his calls or choose favorites, I think that these are the three that made him most proud.

CELTIC-NATION

In 1953, Johnny Most accepted team owner Walter Brown’s offer to become the Celtics’ play-by-play announcer. Mr. Brown’s generosity was legendary, even as the team struggled during those early years. Please tell me a little about Mr. Brown, his family, and his relationship with Johnny Most?

JM

I barely new Mr. Brown because I was so young when he passed away, but even today I feel like I know him. And that’s because dad spoke so highly of him. Walter Brown poured everything he had into making the Boston Celtics successful, and in that respect my dad was a lot like him. They were both very passionate about the Celtics. Everyone who worked for Walter Brown knew how much he loved his team. Everyone who listened to dad on the radio knew how much he cared about the players.

Because he was such an integral piece of the Boston Celtics, we decided to include a chapter on Walter Brown in the book. It seemed like the perfect way to remind fans of how great he was. Dad had a tremendous amount of respect for him, and he would have insisted on including him in “Voice of the Celtics”.

MC

To a man, the players thought the world of the guy. He helped Johnny financially on a couple of occasions, and he did the same for many of the players as well. He was a man of his word, which meant a great deal to everyone – the players, the businessmen that he dealt with, and the other owners in the league. In many ways he was ahead of his time.

CELTIC-NATION

Johnny Most coined many great nicknames, from “Jungle” Jim in honor of Celtic great Jim Loscutoff, to “McFilthy” and “McNasty”, the not-so-subtle jabs at Washington’s Rick Mahorn and Jeff Ruland. Which Celtic players were among Mr. Most’s most revered, and which opponents were among his most reviled?

JM

When it came to the Celtics, dad would never name his five favorite players. He would never go there. He didn’t revere one more than the other – he rooted for them all, and he considered all of them his buddies. He would root just as hard – if not harder – for the player on the end of the bench as he would a star like Larry Bird or Bill Russell. To him, he took a great interest in all of the players and not just the ones who made the headlines, so he would never name an all-Celtics team.

In terms of villains, Bill Laimbeer certainly ranks at the top of the list. Dad thought he was a dirty player, and he hated the way he flopped to get calls. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wasn’t a favorite, either, but he didn’t come close to Wilt Chamberlain in the villain department. He thought Wilt was soft, and that he was more concerned with getting his points than winning championships. I think part of it was dad’s respect for Russell; Bill Russell was incomparable, and I think dad resented the publicity that Wilt got for all of those points and rebounds.

Almost everyone who played against the Celtics were villains, but dad definitely had no love for Rudy LaRusso, Dennis Rodman, Ralph Sampson and Rick Barry. He hated Rodman’s showmanship, and thought he was hot dog. Ralph got into that fight with Jerry Sichting during the 1986 NBA Finals. Dad hated Barry as a player, but the two of them got along really well off of the court.

MC

I think Johnny hated Isiah Thomas the most. Johnny thought he was a phony, and he thought he was as dirty as any of the Bad Boys on those Pistons teams. So there was a genuine dislike for Isiah Thomas. He thought Isiah put on this fake act, with that impish grin and humble persona, and he thought that it was put to use on the officials.

Wilt is definitely on the list. Johnny knew Wilt very early on. He later offered him advice on how to succeed in the NBA, but Wilt acted like he didn’t know him. That hurt Johnny, and I don’t think he never forgave Wilt for it.

CELTIC-NATION

Players such as Dennis Johnson were hated when playing against the Celtics, but that all changed once they donned the green-and-white. If Johnny Most were calling games today, how do you think he would feel about (former Celtic) Antoine Walker’s wiggle?

JM

I don’t know if it would have been my dad’s favorite [laughs]. He didn’t like trash-talking and showboating, and deep down I think the wiggle would have bothered him.

MC

I don’t know how he’d like it. When Johnny first started broadcasting, those things just didn’t happen. I’m not singling out Antoine Walker, because Kevin McHale and Larry Bird were world class trash-talkers. But it was different with them – they didn’t do it in such an overt way, whereas Walker is more demonstrative.

CELTIC-NATION

Everyone associated with the Boston Celtics has a story about Red Auerbach. Please tell me a little about Johnny’s relationship with Red, and please share a favorite story about these two great men.

JM

Dad spoke as highly about Red Auerbach as he did about Walter Brown, and I heard nothing but good things about him as far back as I can remember. They were friends first, even though Red was his boss. There were some common bonds between them - they both joined the Celtics in the early 50s, they were both Jewish, and they were both from New York. And Red always treated dad like a part of the team; to him, dad wasn’t just a radio personality. He was a part of the Celtics family.

When dad auditioned for the job, Red downplayed the fact that he wanted him more than any of the others. It was Red who helped convince Walter Brown to offer dad the job – Walter loved dad’s audition, but wasn’t sure if the Boston fans would take to someone from New York. That’s when Red reminded Walter that he [Red] was from New York, and that he was doing okay as the coach of the Celtics. But when Red called dad, he acted as if Walter had talked Red into making the choice [laughs].

MC

Johnny looked at Red as a father figure. There was a lot of mutual admiration. Red wanted Johnny after broadcasting one game – but as Jamie mentioned, Red needed Walter Brown’s approval. And Walter had serious reservations, because Johnny was from New York. That didn’t phase Red at all. He talked Walter into it, called Johnny with the news, and then negotiated a contract.

CELTIC-NATION

Celtics fans everywhere are familiar with the heartfelt refrain, “We love ya, Cooz.” Please take me back to December 3rd, 1990, and share with me that wonderful night “High high high above courtside”, when the Boston Celtics retired Mr. Most’s microphone.

JM

Dad was a tough guy who didn’t shed many tears. To be on that court with him, to see those tears, and to hear that standing ovation…it was one of the most emotional things I’ve ever experienced, and I know that it was much more difficult for him. It showed the depth of the love affair between dad and the fans. And to have Larry Bird come out and give him a piece of the parquet floor – it was a very special night, and one of the hardest things my dad ever had to go through.

MC

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to be there for that ceremony; my mother was dying of terminal cancer, and I was with her. I’ve heard Jamie talk about it, and I’ve heard other stories from people who were there, and I know that it was a very emotional moment.

CELTIC-NATION

The expressions coined by Johnny Most represent a lexicon basketball’s most descriptive color, uniquely original and instantly identifiable. “Fiddles and diddles”, “From downtown”, and “Stops and pops” are just a few examples of his brilliance. Given today’s high-tech, cookie-cutter approach to broadcasting, do you think we’ll ever see another Johnny Most?

JM

I’ve sensed a trend in recent years where local radio announcers are backing the local teams with more emotion. People want to have the broadcaster on their side, rooting for their team, but I just don’t believe anyone will be able to duplicate what my dad did with the Celtics. That’s just who he was – a fan of the team, and the one with the best seat in the house. He hated phonies, and he wasn’t going to be one. He was going to root for his team, and he didn’t care if people called him a ‘homer’. He stayed true to himself, and in his mind that was the most important thing.

MC

No, I don’t think we’ll ever see another Johnny Most. His style was pure emotion, which you can find today, but there was nothing artificial about the way he called the games. He loved his team. You could tell that just by listening to him for a few moments. Bob Cousy once said that Johnny’s broadcasts brought people to the games, and this was back when the average fan felt that Holy Cross could beat the Boston Celtics. Johnny’s unique style made people take an interest in the team, and he loved the team so much that you ended up loving them, too.

The most important point that I would like to get across with these books is that Johnny Most belongs in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. To date, the only broadcaster voted into the Hall of Fame has been Chick Hearn. Johnny was an original, an NBA pioneer, and a symbol of the Boston Celtics. His calls will be replayed for many years to come.

留言列表

留言列表